Year 8 diagnostic tests: let's make them worthwhile

Monday 19 January 2026

This blog post was first published in SecEd on Monday 5 January 2026.

This blog post was first published in SecEd on Monday 5 January 2026.

The Curriculum and Assessment Review (CAR) recently published its final report. It recommended new diagnostic maths and English tests in Year 8. But what might these diagnostic tests look like?

Let’s start with a subtle but vital distinction: screening tests versus diagnostic tests. Think back to 2021: mandatory lateral flow testing and permanently inflamed nostrils. In effect, we were screening the school population–sorting people into two groups (Covid-havers/non-Covid-havers) to allow targeted interventions instead of generalised ones, like lockdowns.

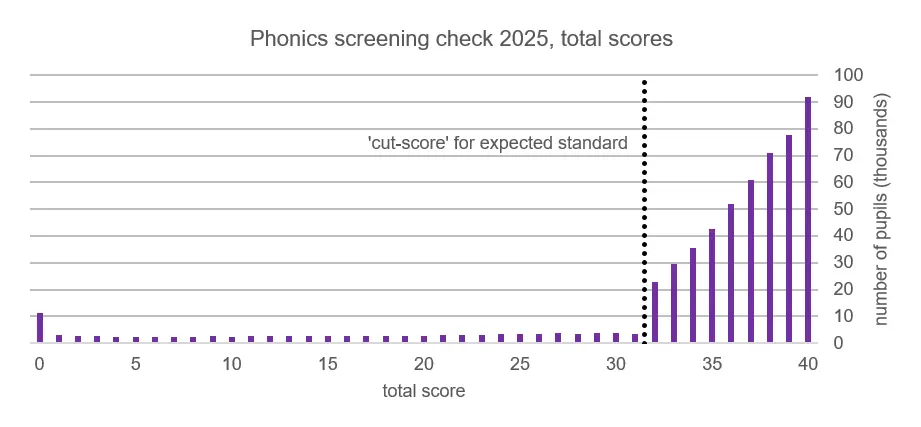

The most prominent screening check is the statutory Year 1 phonics screening check (PSC). It consists of 40 words or pseudo-words (words that appear to be actual words, but have no real meaning (e.g. ghib, quog…) to be read aloud. Its purpose is to screen for pupils who have not reached a predetermined standard in phonics. This explains its unusual score distribution:

A remarkable 92,056 pupils achieved full marks in the 2025 PSC. No fewer than 240,747 ‘dropped’ two marks or fewer. For these pupils, the check provides limited useful information. How would they have done if the test had featured harder words (phrizumph?) We don’t know. It doesn’t matter. This is a screening test: it is designed to provide a single, reliable ‘cut-score’ (typically 32 out of 40), below which pupils are adjudged to need extra help with phonics.

So, do we need a screening test at Year 8? The short answer is no, but it’s worth going into the reasons why not because it helps crystallise what a diagnostic test (as recommended by the CAR) would need to achieve. To keep things simple, let’s focus on reading.

The first challenge facing a Year 8 screening test would be the amount of content to cover. Year 8 reading is much wider than Year 1 reading (let alone Year 1 phonics). More to assess means a longer test.

Secondly, attainment gaps are much wider by Year 8. Some students still struggle with phonics; others read classic novels at bedtime. Imagine a test whose purpose is simply to identify those needing extra support, perhaps those who risk not achieving English GCSE grade 4. This group is huge (perhaps 200,000 students) and diverse: some will miss out only narrowly, while others (perhaps 30,000) will not reach grade 1. A diagnostic assessment will only be useful if it can differentiate within this category.

Finally, Year 8 pupils have plenty of assessment data already on file. Schools generally know who is falling behind. To help schools, a Year 8 test must be diagnostic. That means it must:

- show teachers where weaknesses exist, not just who needs support

- provide reliable, nationally benchmarked outcomes for everyone, without losing focus on those slipping behind

- comprehensively cover the core skills that students need to make progress.

This would be easy if the test could be eight hours long. In real life, however, a traditional test may struggle to be both manageable and usefully diagnostic.

One possible solution has already been adopted nationwide in Wales, Scotland and Australia: computer adaptive tests (CATs). CATs adapt based on the pupil’s responses, so they can be shorter without being less informative. Whereas on a paper test weaker students spend most of their time answering questions that are much too hard for them (dispiritingly, uninformatively), a CAT can direct them to more appropriate material that reveals both what they can do and where they need more help.

Regardless of the type of test adopted (linear or adaptive, online or on paper), what really makes a test diagnostic is how outcomes are used. Key Stage 3 teachers in England currently use a patchwork of assessments, sometimes self-generated, sometimes externally sourced. Often, all they have time to do is mark a test and generate a score, assembling impressionistic insights as they go. Diagnostically, this leaves a mountain of information ‘on the table’. Was performance (individually or collectively) weaker in particular areas? Did particular responses reveal specific misconceptions? A well-designed diagnostic test, thoroughly trialled and analysed in advance, can answer these questions richly and reliably (and, in the case of a CAT, instantaneously, without marking) via detailed reporting at student, class and school levels.

There are many pitfalls to avoid. In particular, detailed reporting can encourage the overinterpretation of statistically insignificant differences, so teachers should be given guidance to help them distinguish the wood from the trees. Overall, however, diagnostic testing at Year 8 has the potential to highlight weaknesses, enrich teacher information, and support students to keep on track during those vital early years of secondary education.