20-21 school funding allocations and catch-up support in England

Monday 27 July 2020

Last week the government announced school funding allocations for the 20-21 academic year in England. NFER Economist Jenna Julius explores how this will be distributed and considers if additional Covid-19 funding will be enough to help more disadvantaged children catch-up.

Last week, the government continued its commitment to “levelling up” school funding by announcing that each secondary school will receive a minimum of £5,150 per pupil and each primary a minimum of £4,000 per pupil under the national funding formula from 2021, up from the £5,000 and £3,750 respectively in 2020.

This policy of “levelling up” is not, however, intended to increase the proportion of funding going to more deprived schools (where deprivation is measured by the number of disadvantaged pupils). The National Funding Formula (NFF) had been designed such that more deprived schools receive higher levels of funding than other schools. As a result, the schools which stand to experience the largest increases in funding from “levelling up” are those serving more affluent communities, while more deprived schools experience smaller increases.

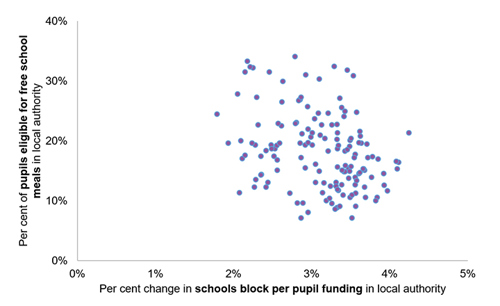

Indeed, the latest increase in schools’ block funding per pupil by local authority – which has resulted from both the “levelling up” policy and other changes to the National Funding Formula – is unrelated to the share of disadvantage pupils (as measured by the per cent of pupils eligible for free school meals) in that local authority. In other words, increases in school funding are currently being distributed across local authorities irrespective of the level of disadvantage.

There is no relationship between the latest increase (from 2020-21 to 2021-22) in school funding and disadvantage

Is now the right time for levelling up?

The evidence suggests this should be a time to provide a larger share of funds to schools with high numbers of disadvantaged children to help their pupils’ catch-up academically, and not to provide a higher proportion of funding to schools with few disadvantaged children.

When schools re-open in September, pupils who have spent little or no time engaging in remote learning – who are disproportionally from less affluent backgrounds – will need substantial support catching up with their peers. While many pupils have fallen behind during the pandemic, fewer pupils have engaged with education in more deprived schools. A recent NFER survey of over 3,000 teachers and school leaders found that 30 per cent of pupils in the most deprived schools were reported to have returned their last piece of school work, compared to 49 per cent of pupils in the least deprived schools. So, there is a definite need for catch-up help across the whole population, but with more support for those most affected.

On top of this, more deprived schools are not getting additional funding relative to other schools to support “catch-up” activities. The £650 million of the government’s £1 billion “catch-up” fund which is being allocated directly to schools is not dependent on the levels of disadvantage among pupils. Further, the 5.5 per cent increase in salaries for newly qualified teachers, which has just been announced, is likely to disproportionately impact more deprived schools that tend to employ more newly or recently qualified teachers (Allen and Sims, 2018). While this increase in salaries will help ease teacher recruitment and retention challenges, it may leave more deprived schools with less funding to support their pupils in catching up.

One area of encouragement though is that schools with high levels of disadvantaged children are likely to benefit more from the National Tutoring Programme (NTP), which will be available to support disadvantaged pupils across schools. There is extensive evidence on the impact of tutoring on helping pupils’ catch-up. A total of £350 million is available through the NTP – which works out at roughly £250 per disadvantaged child, covering the costs of approximately a term of small group tutoring. This fund will also be topped up by schools who will subsidise at least 25 per cent of programme costs. But, it is not clear yet whether this will be sufficient to close the learning gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers created by the pandemic, and deprived schools may require additional funding.

With learning gaps for disadvantaged pupils likely to persist for some time, the government’s approach to school funding needs to focus more on catching up rather than their version of ‘levelling up’ to ensure that all pupils, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, have the opportunity to reach their potential.