Are secondary free schools really achieving what they’re supposed to?

Wednesday 15 November 2017

This opinion piece first appeared in TES on Tuesday 14 November 2017.

A key part of the 2010 Coalition Government’s education strategy, free schools were introduced to create a more autonomous and self-improving school system by driving up standards through greater school choice and increased local competition. However, free schools have attracted a lot of controversy since their inception, with some commentators claiming they are expensive and wasteful, and set up in places where there is surplus capacity, while supporters say they are located in areas of need and provide a better quality of education than local authority schools. Who is right? We explore some of these issues here and ask why so much of the new provision has happened in London.

The first free schools were set up in 2011, following the passing of the 2010 Academics Act. By September 2017, some 311 primary and secondary free schools had opened (excluding UTCs, studio schools, 16-19, special and alternative provision free schools). Nine of these have closed since opening.

One of the burning questions that friends and foes of free schools often ask is whether pupils who go to free schools do better than similar pupils who go to other schools? Up until now, we have not been able to answer this question due to a lack of data, but with the first cohort of pupils in the earliest secondary free schools taking their GCSEs in 2015/16, some early indications are emerging.

NFER compared free school pupils to a matched group of pupils who went to other schools and found some evidence that early Key Stage 4 attainment results indicate positive outcomes for free schools. However, we believe it is still too early to provide a robust assessment of the progress and attainment of free school pupils due to the small number of free schools which currently have Key Stage 4 results available, especially as sensitivity analysis has indicated that the way schools and pupils are matched has a substantial effect on results. NFER will use 2016/17 data to explore this further in a free schools report which we will publish in the New Year.

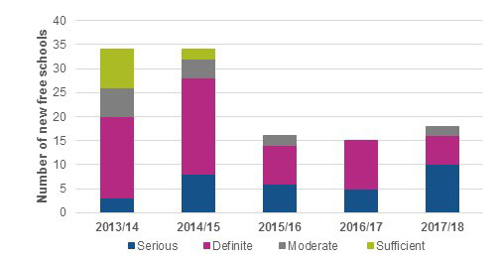

Another question that has dogged the free school programme since its inception is whether free schools are being set up in areas where they are most needed. Demand for secondary places is set to increase by 320,000 by 2020/21 so it will be necessary to generate more school capacity. However, in 2013, the National Audit Office reported that free schools were not always being set up in areas of greatest need for pupil places. Our analysis of secondary free schools suggests that since 2014, free schools have opened in areas where demand in five years’ time is forecast to exceed available capacity.

Figure 1: Secondary free schools have largely been set up in areas where forecast demand in 5 years exceeds available capacity

Note: ‘Serious’ need is where demand in 5 years exceeds available capacity by 20% or more; ‘Definite’ need is where demand exceeds capacity by 5% up to 20%; ‘Moderate’ need is where demand is between +/- 5% of available capacity and ‘Sufficient’ is where future demand is 95% or less of available capacity.

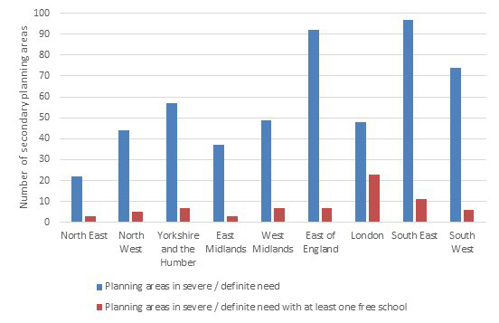

London appears to have benefitted far more than other regions of the country from the free schools programme. Despite this region only having 14 per cent of the country’s secondary schools, 30 per cent of the secondary free schools that are currently open are in London. In contrast, East Midlands and the North East only have 4 and 3 per cent, respectively.

Why is this? One likely explanation is that London is forecast to have the highest growth in secondary pupil numbers by 2020/21. Additionally, despite London having the smallest number of secondary planning areas, nearly all were forecast as being in serious or definite need when the free schools were set up, which may have brought the matter into sharper focus. What is clear though is that many other regions of the country have similar or greater numbers of planning areas which are forecast to be facing a severe or definite need in the next five years. Only 10 per cent of the under-capacity planning areas in regions other than London have benefitted from a new secondary free school, compared to nearly half of the planning areas with a severe or definite need in London.

Figure 2: London has benefitted disproportionately from the free schools programme

Of course, opening up a new free school is not the only way of managing a lack of capacity, but free schools may be the only way to increase capacity in London, given the physical constraints on expansion of existing schools. It will be important to monitor their performance closely as more results become available. The government will need to ensure that there are sufficient places available for pupils across the country – whether that be through the establishment of new free schools, or the expansion of existing schools – to cater for an increase in secondary pupil numbers over the next 5 years.

NFER will be publishing more analysis about both primary and secondary free schools in the first quarter of 2018.