Evidence in education – a lever for professional autonomy?

Monday 3 February 2014

‘We need teachers, not civil servants to lead the teaching profession’. This was one particularly memorable quote from an event that the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) hosted last week with the Coalition for Evidence-based Education (CEBE):‘Linking evidence and practice: what works? What next?

A former Director-General at the Department for Education Jon Coles – and now head of the United Learning group of schools – asked us to imagine two scenarios:

- a civil servant tells a surgeon that she should adopt a new approach to key-hole surgery

- a civil servant tells a primary teacher that he should teach synthetic phonics to all pupils.

Why does the first scenario seem implausible, yet the second is reality?

The medical analogy has been overworked, but it is true to say that medics have substantial evidence to draw on when making clinical decisions. Teachers, in contrast, have a less well established evidence base to support their position.

I don’t think that anyone at our event disagreed with this … and it was an energetic affair with representatives from right across the education sector. Applied well, evidence can increase the profession’s authority and voice, and potentially free it from political interference.

But, there are differences of opinion about how to achieve this goal and about what evidence-informed practice means.

What is evidence-informed practice?

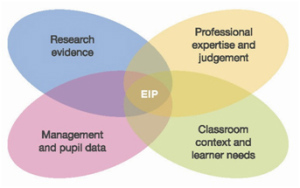

Let me say that I am not in favour of a ‘dogmatic’ view of teachers basing their teaching entirely on what is ‘proven to work’ through research. I think a nuanced view is more helpful. Our recent review and NFER Thinks paper both recognise that teachers use a variety of different forms of evidence in their day-to-day practice. It is the interaction between these that interests me.

Figure 1 - Evidence-informed practice

We know that teachers apply professional judgement, differentiate their practice, and often use pupil performance data to inform decisions. But we also know that research evidence is not consistently added to the mix. This is illustrated in our literature review, which found only a few concrete examples of effective research application in practice. This is not to lay any kind of ‘blame’. The question is, what currently prevents more widespread application?

What prevents greater use of research evidence?

On the demand side, teachers have to want research evidence and believe that it will not undermine their professional autonomy. They also need opportunities (including the time and skill) to seek it out, interpret it, and decide how to apply it.

On the supply side, research commissioners, policymakers and researchers face various challenges in ensuring that relevant, high-quality, evidence is available and accessible for schools.

An additional challenge is the increasingly decentralised and autonomous education system: how can we achieve change across the whole education system, rather than isolated pockets of good practice?

What are the potential solutions?

Our NFER Thinks paper identifies a variety of ‘levers’ that could enable change throughout the education system, rather than evidence-use being confined solely to a small number of settings or aspects of practice. We argue that the demand for research can be enhanced through:

- leadership by the organisations that continue to have national influence in schools, such as school senior-leadership associations (the NAHT and ASCL), local authorities, academy chains and teaching schools

- incorporation of research into teachers’ whole-career development (through initial teacher training, continuing professional development and the National Professional Qualification for Headship). Programmes themselves need to be evidence informed, and more training could be offered in the skills of engaging critically with research

- incorporation of a ‘research-use’ requirement into teachers’ professional standards (national performance management guidelines, and teaching and learning responsibility point criteria) and into school accountability measures (Ofsted should have a role in guiding and supporting schools in the effective use of evidence, and there is scope for the accreditation of successful practice too, through schemes such as NFER’s Research Mark).

In terms of supply, we argue that schools’ needs and interests should have greater influence on what research gets commissioned. We want future research commissions to build on the existing evidence base… and we believe that standards should be developed to help teachers assess the merits of different sources of evidence.

None of this is easy. Many approaches have been tried before but have had less impact than intended. The large-scale ESRC-funded Teaching and Learning Research Programme, described in our review, is one example of this.

As a sector, we need to agree how to take these, and other, ideas forward. Then we can help teachers to acquire that valuable ‘lever’ for greater professional autonomy – for the positive good of schools and learners.

This blog post has also been posted on the Alliance for Useful Evidence blog.