How many teachers are not able to work in school because they, or a family member, are at higher risk from Covid-19?

Thursday 15 June 2023

How many teachers are working and what is stopping those who aren’t?

Earlier this month, NFER and the Nuffield Foundation published new insights from a survey of senior leaders on schools’ preparations for more pupils to return to school, exploring the extent of the challenge the disruption poses. The survey shows that in May schools were operating with just 75 per cent of their normal teaching capacity. In addition, school leaders report that an average of 29 per cent of the available full-time equivalent teaching capacity is only able to work from home.

There are several reasons why teachers might be unable to work in school, at all, or as much. The two major reasons are likely to be childcare and teachers shielding themselves or others in their household from potential infection and others are likely to include illness, compassionate leave and a lack of adequate IT facilities at home. A lack of childcare is likely to be a significant reason in the short-term, but is unlikely to be a persistent one for most teachers with school-age children as they can use keyworker school provision once they are required to return to work in school. Early years settings reopening will also be able to support those with pre-school children.

However, shielding is an issue that is likely to remain very significant for a long time yet. Individuals at moderate or high risk (as defined in NHS advice) of becoming seriously ill from Covid-19 are likely to remain shielding until there is a vaccine, or transmission rates fade away to negligible levels. Neither of these seems likely to happen in the next few months.

The Department for Education’s (DfE) guidance on wider opening sets out advice on what schools should advise teachers and other staff within these groups to do as schools open more widely. It also sets out what staff who live in a household with someone in one of these at-risk groups, but may not be at risk themselves, should be advised to do.

Those who are themselves, or live with someone, at high risk should be supported to work from home, as well as those who are at moderate risk themselves if stringent social distancing cannot be adhered to in school. The guidance advises that those who live with someone at moderate risk, but are themselves at low risk, can attend work.

How many teachers are in these at-risk groups?

We use data from the Understanding Society April 2020 Covid-19 survey to estimate the size of these groups for the teacher population in England, using their risk level according to the underlying conditions they report having. It is based on a small sample of 240 teachers, so estimates should be treated with a high degree of caution. We use 95 per cent confidence intervals to show the extent of uncertainty around our estimates.

The fact that Understanding Society is a household-level survey means that we can explore both individual and household member risk levels. However, as there is likely to be non-response to the Covid-19 survey among other members of the household, the number of teachers in households with people at risk are likely to be underestimated. It is also likely to be an underestimate of household risk because the survey does not include assessments of the health conditions among children under age 16 in the household. There are other methodological limitations that affect the interpretation of this analysis, which are described in the footnotes.

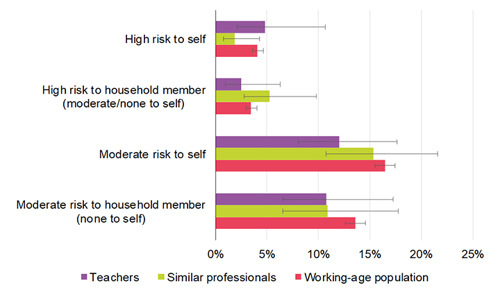

In total, at least 30 per cent of teachers are themselves, or have a household member, in a high or moderate risk category. Around five per cent of teachers are themselves in the high-risk category and have been advised by the NHS to shield. At least a further three per cent are in a household with a family member who is in the high-risk category. Around 12 per cent are in the moderate-risk category and at least a further 11 per cent are at low risk but have a household member in the moderate-risk category.

All these proportions for teachers are similar to the proportions among similar individuals in other professions and the whole working-age population – there are some differences but all are within the fairly wide margins of error.

At least 30 per cent of teachers are themselves, or have a household member, in a high or moderate risk category

Source: NFER analysis of Understanding Society Wave 9 and April Covid-19 survey.

Note: the coloured bars show the estimated proportion among the working-age population/ professionals / teachers in England; the black crossbars shows the 95 per cent confidence interval around each estimate. Similar professionals are individuals in any professional occupation, weighted to match the sex, age, highest qualification and region distributions of the teacher population in England. Working-age population are adults age 16-65 in England.

This analysis suggests that DfE’s advice implies that around 20 per cent of the teacher workforce should be supported to work from home. At least a further ten per cent of teachers ‘can attend work’ according to the DfE guidance because they are at low risk themselves but live with someone at moderate risk. However, in practice many of these teachers may be very reluctant to attend work on the school site. School leaders may take a sympathetic view of these teachers’ wishes if they strongly object to teaching on site.

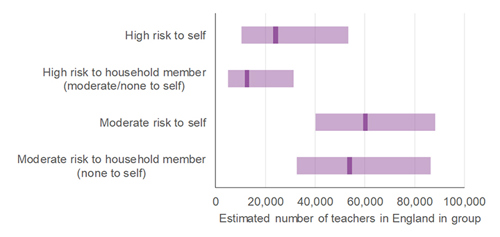

Scaling up these proportions to the national level using total teacher numbers from the School Workforce Census (500,000) shows the full extent of the challenge this poses for teaching capacity. While there is considerable uncertainty in these estimates, as shown by the 95 per cent confidence intervals below, we estimate that:

- 24,000 teachers are in the high-risk category and are strongly advised not to attend work, though may work at home

- 73,000 teachers are either at moderate risk or live with someone at high risk, so should be supported to work from home

- 54,000 teachers live with someone at moderate risk, so while they are advised to attend work they may be reluctant to do so.

Around 100,000 teachers are advised to be supported to work from home and 50,000 may be reluctant to work in school because of risks to a family member’s health

Source: NFER analysis of Understanding Society Wave 9 and April Covid-19 survey, and School Workforce Census.

Note: Dark purple line shows the estimated numbers; the purple bar shows the 95 per cent confidence interval.

In total, around 100,000 teachers are being advised to be supported to work from home, while a further 50,000 are in the group advised to attend work but who may be reluctant to do so because of risks to a family member’s health.

To put these numbers in perspective, around 26-29,000 Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs) enter state-sector teaching each year. As we reported in our 2020 Teacher Labour Market in England report (published 5 June), the teacher supply challenge that the school system faced before the pandemic means there is limited additional teaching capacity sitting around waiting to be employed.

What are the implications for schools and policy?

Our analysis suggests that schools face a substantial loss of 20-30 per cent of their on-site teaching capacity that will limit the provision schools can offer as they open more widely. This capacity constraint is likely to persist, and comes at a time when schools need more teaching capacity, due to both smaller class sizes in school and the need to continue providing for teaching pupils who are not yet returning to school.

The school system was already facing a teacher supply challenge, meaning there is not a ready supply of teachers who could easily fill this gap. Schools also have limited budget to recruit extra staff to fill gaps in their in-school teaching. The recession induced by Covid-19 does appear to be encouraging more teachers to stay in teaching, at least for the short-term, and more teachers to apply to teacher training. However, the number of at-risk teachers who are shielding is likely to outweigh these gains in the short-term and severely constrain teaching capacity for the foreseeable future.

The Government should take account of these capacity constraints that schools face when planning what to advise schools to provide when they are encouraged to open more widely. Since different schools, and departments within secondary schools, will be more or less affected, any guidance should also be sufficiently flexible to support the schools who happen to be most affected. It may also be necessary to consider how policy can support and enable resource-sharing between schools, to assist schools who are disproportionately affected.

On Tuesday and Friday, NFER will publish the second and third reports in our Nuffield Foundation funded series focusing on schools’ responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Both reports will be available to read and download here.