Implementation factors that support remote teaching: guidance for schools and colleges

Thursday 24 November 2022

The global outbreak of Covid-19 and the subsequent partial school closures significantly disrupted education in England. The national lockdown periods in 2020 and 2021 created an unprecedented need for remote teaching and learning solutions.

The global outbreak of Covid-19 and the subsequent partial school closures significantly disrupted education in England. The national lockdown periods in 2020 and 2021 created an unprecedented need for remote teaching and learning solutions.

As part of a DfE-commissioned qualitative study, we explored the approaches used by 16 case-study schools and colleges to delivering remote teaching. For many of the schools and colleges we spoke to, live remote teaching was a novel approach introduced as part of an emergency response to the pandemic. This blog post discusses some of the key learning points from schools’ and colleges’ journeys to developing a remote teaching offer.

Remote teaching can take different forms, but for the purposes of our study, remote teaching was defined as ‘a teacher teaching a live lesson from a different location to some or all of the pupils’. While our study was based on relatively small-scale qualitative research, the findings, which should be of interest to policymakers and senior leaders, add to the evidence base on the challenges associated with remote teaching and the factors that teachers feel supports its effective delivery.

What worked well about using EdTech tools for remote teaching?

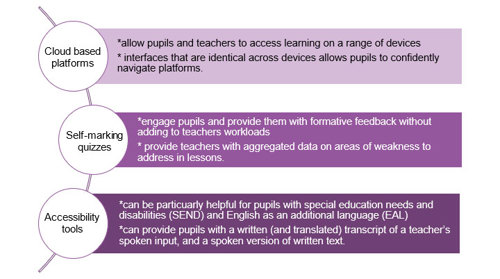

Schools and colleges reported that EdTech worked well to support remote teaching when it was user-friendly, where data was stored ‘in the cloud’ rather than on a local computer, where it was consistent across different devices (e.g. laptops and mobile phones) and where it enabled integration between applications and platforms. Teachers also spoke of the benefits of using self-marking quizzes and accessibility tools for engaging pupils (see the figure below).

However, there is a paradox around live remote teaching

While it has the potential to be more engaging than other forms of remote education (such as where pupils complete tasks independently with only pre-recorded content), teachers spoke of the challenges of keeping students engaged. They faced challenges around pupils being camera shy and reluctant to contribute to discussions online compared to in person. While the use of smart retrieval quizzes had helped to increase pupil engagement, these approaches had not fully overcome these issues.

In addition, some teachers found the pedagogy required to deliver remote lessons to be different to teaching in a classroom. This resulted in some teachers feeling ‘de-skilled’ and meant they lacked the confidence to deliver remote lessons to the same quality as their in-person delivery.

So, what can schools and colleges do to support successful implementation of remote teaching?

Our research identified four further learning points that schools and colleges might want to consider should they need to deliver remote teaching in the future.

- A digital strategy was associated with a consistent approach to remote teaching

Schools and colleges emphasised the importance of developing a digital strategy to establish expectations for teachers and pupils regarding the use of remote teaching and to ensure consistency across subjects and phases. Given the continuing role played by EdTech in supporting education recovery programmes, schools and colleges should consider developing their digital strategies alongside their Covid recovery strategies.

Given moves to avoid large scale school closures in the future, it is likely that hybrid provision (whereby schools and colleges are simultaneously teaching pupils both face-to-face in class and remotely at another location), rather than everyone being online, is more likely to be the focus of any remote teaching in the future. However, teachers told us this poses additional pedagogic challenges, and therefore this approach needs further consideration within schools’ and colleges’ digital planning.

- High-quality training can help pupils and teachers get the most out of remote teaching

Many of the teachers we spoke to felt that training for their staff was critical. Rather than just providing generic instructions, training focused on how to use the more advanced features of their chosen tools, such as break out rooms within video-conferencing software, and digital whiteboards. Some schools and colleges also provided training for pupils, including on how to access, and share documents, use interactive features (such as emojis and the ‘raise hand tool’), as well as guidance on online etiquette.

- Approaches to remote teaching need to work for everyone

To make their approaches more accessible and effective for more learners, several teachers described how they made adaptations to their early approaches to delivering remote teaching. For example, one primary school trust had the ambition of replicating the whole-school day online, but found that this approach was unfeasible, despite some parents wanting the structure of a full timetabled day.

Some interviewees commented on the challenges of delivering remote education to younger children, particularly those in Reception and Year 1, while others found that remote teaching did not work well for some pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). These experiences led teachers to reflect on the challenges of offering a ‘one-size-fits-all approach’, and of the need to match the school’s or college’s ambitions for remote teaching with the needs and preferences of pupils and their families.

- Teaching quality matters most

Despite the hyperbole regarding the future role of EdTech in teaching, many of the teachers we spoke to recognised the need for pupils to have a varied diet of online and offline activities, and many schools and colleges planned to downsize their remote teaching offer or had already done so.

While the advent of new technologies such as artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented realities may have already become a reality for some schools and colleges, we agree with previous research, which suggests that the quality of teaching is more important than how lessons are delivered. Indeed, our research suggests it is necessary to upskill teachers, through continuing professional development (CPD) focussed on how to plan and deliver remote and hybrid lessons. This should include guidance on how to adjust lessons to promote engagement through interaction.

The Government remains committed to remote education ‘allowing children to keep pace with their education when in-person attendance in school is impossible’. Our study provides further evidence on the potential uses of remote teaching and how to realise this potential. Future developments in EdTech will need to consider how best to support learners who may experience barriers to accessing remote teaching, including disadvantaged pupils, younger children and pupils with SEND.