Increasing pupil numbers create challenges for secondary schools

Thursday 13 July 2017

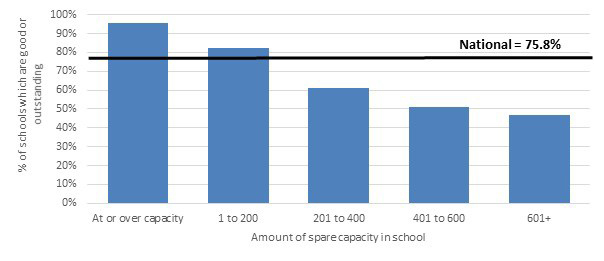

The Government has today published the latest Department for Education (DfE) national pupil projections. They show that state primary and secondary pupil numbers are expected to continue to grow over the coming years. The number of primary pupils will see a small increase of 1.9 per cent between 2017 and 2021, after which it will plateau.

However, secondary schools will see a much larger increase, with the number of full-time equivalent pupils aged up to 15 years projected to increase by 320,000 (+11.4 per cent) by 2021 and to continue to grow until 2025. This significant growth for secondary schools suggests a major challenge ahead and, in this blog post, we look at what this might mean for the sector.

Figure 1: State funded primary and secondary schools: actual/projected pupil numbers

Source: 2017 National Pupil Projections

Firstly, the Government has been planning for rising pupil numbers and has allocated £2.4 billion of capital funding to help prepare for the additional school places needed by 2020, with £1.4 billion ring-fenced for upgrading and improving school buildings. Overall, the Government says it is committing £24 billion to invest in the school estate between 2015 and 2021. But what does this increase in pupil numbers mean in terms of school capacity?

At first glance, there appears to be sufficient capacity in the system, but….

The latest secondary school capacity figures showed that there were 636,462 unfilled places in state secondary schools in May 2016. When set against the 320,000 projected extra pupils aged up to 15 years by 2021, this suggests that there is a healthy buffer of spare places to cope with increased pupil numbers.

This spare capacity is partly related to an increase in the number of state-funded secondary schools since 2012, which totalled 3,382 in January 2017, close to their 2006 level. In particular, some spare capacity is a result of significant investment in secondary free schools which were introduced in 2011, and of which there were 133 in January 2017 (excluding 16-19 free schools).

While it appears there is more than enough spare capacity within the system to cope with increases in pupil numbers, it is more complex than this and the outlook might not be as rosy as it seems for various reasons:

- spare capacity is spread across all secondary school years but the bulk of the growth in applications will be for places in Year 7. We do not know how much of the 636,462 spare capacity is in Year 7 but, as this capacity is likely to be spread across five to seven years depending on whether a school has a sixth form, we might conclude that the available capacity in Year 7 will be several multiples lower

- we do not know from the statistics whether Year 7 spare capacity is located in the areas of the country where it will be needed. If some is not, this is likely to further reduce the amount of spare capacity to support projected growth in pupil numbers

- even though many schools have spare capacity in terms of accommodation, significant planning may be needed to bring this into use as, for example, more teachers will need to be recruited and more equipment and resources may be required.

Will parents want to send their children to the schools which have the spare capacity?

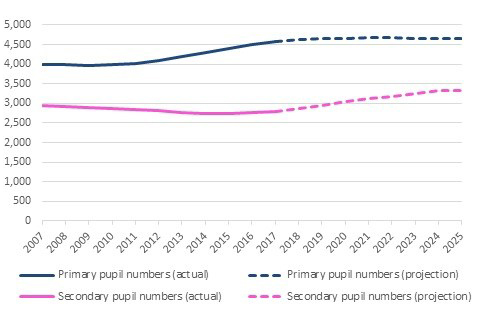

Even if the spare capacity available is in the right year groups and parts of the country, is it available within schools that parents are happy for their children to attend? Our analysis suggests that schools which are at or over capacity are more likely to be judged as good or outstanding by Ofsted, whereas those with greater capacity are less likely to be and therefore may be less attractive to parents. If these are the schools which will meet the rising demand for secondary places, more support will need to be provided to help them to improve.

Figure 2: Percentage of secondary schools that Ofsted has judged as good or outstanding by amount of spare capacity

Source: 2016 School capacity and forecast tables and Ofsted maintained schools and academies inspection outcomes March 2016

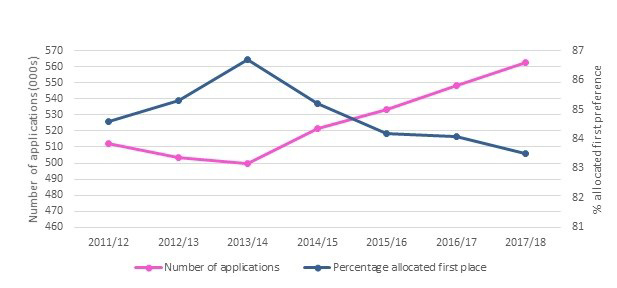

As demand increases, will fewer parents be allocated a place at their preferred school?

Related to school capacity is the allocation of school places and, with increasing pupil numbers and greater competition for places, more parents/carers may be dissatisfied with the school at which their child is allocated a place. Between 2013 and 2016, applications for secondary school places increased by more than 60,000, during which time the number of applicants allocated their first preference fell by three per cent. This issue may become more acute in some areas of high demand such as London where, for example, in Hammersmith and Fulham, just over half of applicants (53.6 per cent) were allocated their first preference in 2017/18. If this trend continues as pupil numbers increase, it may result in more disappointed parents/carers, especially if some of the rising demand is met by allocating spare capacity in schools which Ofsted has judged to be other than good or outstanding.

Figure 3: Trends in number of secondary school applications and percentage being allocated their first preference

Source: Secondary and primary school applications and offers: 2017

And what about forthcoming funding challenges?

How secondary schools manage the increase in pupil numbers also needs to be placed within the context of a reduction in funding per pupil in real terms. The National Audit Office report on the financial sustainability of schools published in December 2016 reported that mainstream schools would need to find £3 billion in efficiency savings by 2019-20. This equates to around an eight per cent reduction per pupil between 2014-15 and 2019-20. This figure does not take account of potential funding reductions resulting from the new school funding formula on which the picture is still unclear. Although school costs may not rise directly in line with pupil numbers, schools will be expected to teach more pupils with less funding per capita in real terms.

Yet more teachers will be needed within the context of ongoing issues of teacher supply…

Additional teachers will be needed to accommodate the rising pupil numbers at a time when teacher recruitment and retention is one of the top challenges faced by schools. For example, there have been teacher shortages in physics, mathematics and design and technology for many years and recruitment issues are becoming more acute in these subjects, as well as in computing. This is a result of the numbers of entrants to initial teacher training (ITT) in these subjects being well below target. Schools are also having difficulty recruiting sufficient teachers to start to meet the Government’s target (which is still under consultation) for 90 per cent of pupils to enter GCSEs in English Baccalaureate subjects. This particularly applies to modern foreign language teachers.

Alongside teacher recruitment is the issue of teacher retention with one of the key drivers reported by teachers being workload. Recent data drawn on in a previous NFER blog post shows that the proportion of those leaving secondary teaching (10.4 per cent) exceeds those joining (9.8 per cent) and this is at a time when increasing numbers of teachers are required.

So, in conclusion, the projected increase in pupil numbers, combined with a range of other challenges such as funding and teacher supply, provide policy-makers, educational planners and school leaders with a number of issues to work through. It will be interesting to see how this plays out.