London Callings

Thursday 17 November 2016

Although the proportions of teachers joining and leaving the profession in London is largely balanced, as in the rest of the country, both occur at higher levels in the capital. New NFER analysis finds that, relative to the rest of England, London faces the greatest challenges retaining its school teachers and leaders. A higher share of working-age staff are leaving to teach elsewhere in England or in other London education jobs, or are becoming unemployed.

Recruitment and retention tops the agenda

The teaching workforce is the biggest issue currently facing the education system according to sources as diverse as ATL, Teaching Leaders, Surrey Headteachers and the National Audit Office. The issue is particularly worrying given the rise in new school places that will be needed as pupil numbers increase.

Last November, NFER published ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go?’ an analysis of teaching staff (including school leaders and all education phases) joining and leaving the profession in England, including where they go. The analysis was based on Labour Force Survey (LFS) data for 2001–14 and attracted attention, including from the Education Select Committee. In September of this year, the DfE published regional school workforce data for 2010–15 and NFER published follow-up research on retention: Engaging Teachers.

As NFER is providing evidence to the GLA, we looked at what these three sources together might tell us about teachers in one region, London. There is only a sample of 75 London teachers in the LFS who left the profession in that time, so results should be treated as indicative only.

Understanding London’s teacher workforce

The DfE data shows that London schools are relatively well staffed, with some of the lowest pupil-teacher ratios, especially in primary schools, which saw the biggest fall nationwide from 2010 to 2015. It also shows there are more than twice as many unqualified teachers in London primary schools (seven per cent) than England (three per cent) as a whole, and eight per cent versus six per cent in secondaries.

Our earlier research already highlighted the overall rate of teachers leaving the profession (ten per cent), but inner London has the highest rate (over 12 per cent). Combined with London having the smallest proportion of teachers retiring, this finding means more working-age teachers are leaving. Although our follow-up research on retention had no region-specific analysis, it did find some worrying national trends, with a recent increase in teachers considering leaving (from 17 to 23 per cent).

Recruitment is also a challenge for London, especially for primaries, where there are more than twice as many schools with vacancies or temporary staff (15 per cent) compared to England (seven per cent). However, more teachers join the profession in London (14 per cent) than the rest of the country (11 per cent), a smaller proportion of whom are former teachers returning. London is also a net exporter of teachers to the rest of the country, with ten per cent of London teachers leaving the capital for other schools and eight per cent coming in to London.

This finding suggests London is particularly attractive to new teachers but that many then drift away to teach elsewhere, or away from teaching all together. The Chief Executive of the Ark Academy chain described this in her evidence to the GLA: “We find that we are getting the young teachers who are prepared to come and live like sardines in flat shares and tiny spaces. We can keep those, and they come drawn by the magnet that is London. Our problem is retention”.

The GLA’s ‘Getting Ahead’ programme develops new school leaders and is poised to start its second year. Our research found that nationwide, school leaders are less likely to consider leaving, whereas experienced male teachers are more likely to leave. It also explored the factors that help to retain staff – such as engagement.

Figure 1: London teachers that leave are more likely to stay in education, or be unemployed

We looked at the LFS, to see what London teachers who leave do next. We found that those who left teaching (excluding retirees) were ten percentage points more likely to get a job in the wider London education sector compared to the rest of England, in particular in non-teaching roles, at private schools and as teaching assistants.

By contrast, a smaller proportion took jobs outside education, which is surprising given such a large, lucrative and diverse job market. Although similar proportions of leavers became economically inactive overall, London teachers were more than three times as likely to be unemployed, at 19 per cent versus six per cent nationally.

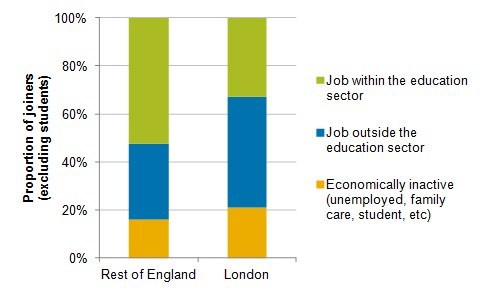

Figure 2: London teachers are more likely to join from outside the sector

At the other end of the teacher career journey, we found that new joiners in London (excluding students) were more likely to come from outside education. Again, a similar proportion were economically inactive, but more than twice as many were previously unemployed (14 per cent vs six per cent). This might suggest unemployment is higher in the capital, yet it is currently 1.5 per cent below the national average. This requires further research over the periods in question.

If they leave, teachers work fewer hours but get paid less

When trying to understand why teachers leave, it seems to be about reducing the hours they work rather than getting more money. On average, teachers reduced their hours by 13 per cent compared to those who stayed in the profession. We found a ten per cent drop in wages overall for teachers leaving the profession both in London and the nation, even when accounting for characteristics such as salary, responsibilities, education phase and age.

So what does this initial analysis tell us about the London workforce? That the London workforce has unique features, that the flow of staff joining and leaving the profession in the capital is higher, that London exports staff elsewhere, and that the leavers who do stay in town tend to stay within the sector. It also highlights some potential risks, with lower retention in London and more leavers becoming unemployed. It’s clear that if London schools are to continue to be international success story, they have to both attract and to retain the staff they need.