Part-time teaching: what can secondary schools learn from the most flexible schools?

Thursday 19 July 2018

In our recent research on teacher retention, we highlighted that increasing part-time and flexible working opportunities for teachers is likely to encourage more teachers to stay in the profession. In this latest blog post we examine what the latest data on the teacher workforce, published last month, tells us about part-time working, and what can be done to support schools to accommodate more part-time and flexible working.

While the prospect of large numbers of full-time teachers moving to part-time on its own presents a risk to teacher supply, there are three main reasons why more and better part-time and flexible working is important for improving teacher retention.

- There is unmet demand for part-time working in the secondary sector, which drives some teachers to leave

The proportion of secondary teachers working part-time has increased from 17 per cent in 2010 to 19 per cent in 2017. However, primary schools have a significantly higher proportion of part-time teachers compared to secondary schools: 27 per cent in 2017. Part of the primary-secondary gap is explained by there being more female teachers in primary schools, more of whom work part-time in both sectors. However, our research shows that a big part of this gap persists even after accounting for differences in the gender distribution. This suggests that there is unmet demand for part-time working among secondary school teachers in particular.

Furthermore, our research has shown that many secondary teachers who leave teaching for another job switch from full-time to part-time work. Among secondary teachers who leave for another job, the proportion working part-time rises by 20 percentage points after leaving, which suggests that this unmet demand for part-time work is partly driving some secondary teachers to leave the profession. It also suggests that more flexible working opportunities may have encouraged some of them to stay.

- Part-time working needs to be a more sustainable option for teachers

The latest teacher retention data shows that the rate of leaving the profession among part-time teachers (13 per cent in 2017) is higher than among full-time teachers (9 per cent). Our research found that the difference in leaving rates between part-time and full-time teachers is even greater in secondary schools, which may indicate that part-time teachers in secondary schools find it more difficult to sustain the demands of part-time working alongside their other responsibilities. Improving retention of part-time teachers would help to ensure that success in accommodating more part-time working for those who want it leads to sustained retention in the profession.

- Lack of flexibility is a barrier to potential returners

Not only is the relative inflexibility of secondary schools having a negative impact on leaving rates, but it is also creating a barrier to re-entry for secondary teachers who wish to return to teaching. Our recent evaluation of the Return to Teaching pilot, which we discussed in our previous blog post last week, identified a lack of part-time and flexible working opportunities as one of the main barriers facing secondary teachers who want to return to the profession.

What can government and school leaders in the secondary sector do to improve the situation?

The current evidence base on what works for schools in making part-time and flexible working opportunities more available is quite limited. Identifying and sharing existing best practice, to provide schools with effective strategies for promoting part-time and flexible working, is therefore crucial for understanding what can be done to make flexible working more available to teachers who want it.

NFER research commissioned by DfE shows that around two-thirds of senior leaders perceive that the complexity of timetabling is the most significant barrier to agreeing part-time or flexible working patterns for teachers. Given the complexity of school timetabling, teachers themselves can also help to enable more flexible working by being flexible on what arrangements they are willing to accept. The challenge faced by school leaders of ensuring the school is fully staffed at all times should be respected by teachers who would like part-time work: not all part-time teachers can have Fridays off.

Nonetheless, it is worth exploring how some schools have managed to overcome barriers to flexible working, such as timetabling, cost and promoting a culture that encourages flexible working. Our analysis of the latest teacher workforce data shows that there is a group of secondary schools with a proportion of part-time teachers that is above average, which are likely to be those that the sector can learn most from.

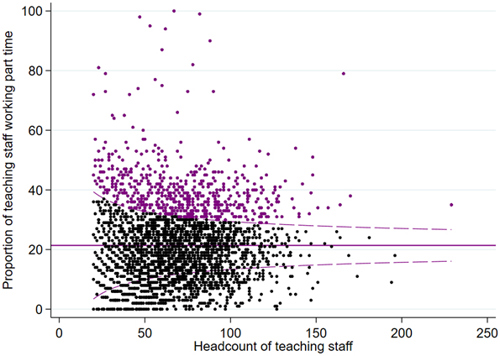

Figure 1 is a ‘funnel plot’, which we use to identify these potential beacons of best practice. Funnel plots have been extensively used in health research to compare relative institutional performance and are being used increasingly in fields such as education.

The figure plots the proportion of teachers who work part-time at a secondary school against the number of teachers in that school. The horizontal purple line shows the average proportion of secondary teachers who work part-time. The funnel plot shows that schools with a small number of teachers have a larger variation in part-time rates, whereas schools with many teachers tend to be less spread out.

Source: School Workforce Census

The relationship between how spread out the data is and the number of teachers there is follows a mathematical formula: the dashed curves show this relationship and are known as ‘control limits’. If differences between schools were exclusively due to random chance, then most of the data points would be plotted within the control limits. In fact, if schools’ part-time rates are due to chance, then we would only expect to see around 80 of the 3,186 schools to be above the control limit. However, the plot identifies 349 schools that are above the control limits, suggesting there are a number of schools outperforming the average (although those with values close to 100% may either have unique circumstances or inaccurate data).

Our analysis therefore suggests that there is at least some scope for secondary schools to learn from the schools that are good at accommodating part-time working for their staff. We believe that sharing best practice in overcoming the barriers to providing flexible working opportunities can go a long way to improving teacher retention issues in the secondary sector in the long-term.

‘Part-time teaching: what can secondary schools learn from the most flexible schools?’ is the fourth and final blog post in our school workforce in England series.