PIRLS 2016 results and the importance of teaching

Tuesday 5 December 2017

24 November 2010 marked a significant day for education. As some four and five year olds were settling into their first term of school, it was also the day that former Secretary of State for Education, Michael Gove, unveiled his plans to overhaul education in England, publishing a new white paper, The Importance of Teaching.

Nearly six years later, a small group of those same four and five year olds represented England in the 2016 round of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) – a study of nine and ten year olds’ reading that has run every five years since 2001 and involves over 50 countries. These children have experienced their entire school education under the coalition and conservative governments and the reforms which began under Michael Gove. The results, published today, will therefore inevitably be viewed as a reflection on the extent to which these reforms have succeeded.

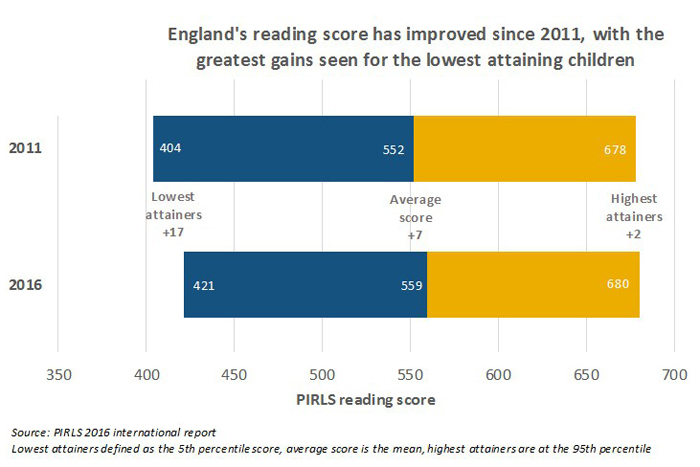

The good news, firstly for our children, and secondly for proponents of the reforms, is that England’s score has seen a statistically significant improvement since the previous PIRLS study in 2011. Furthermore, these gains have been greatest among the lowest attaining children.

This is certainly cause for celebration, and will be a relief for those who may worry about (or have experienced) the disruption that is inevitable during any period of reform. However, the results should also be placed in perspective. Whilst the improvement is statistically significant, in educational terms an improvement of seven points on the PIRLS reading scale is still relatively small. England’s average score of 559 is also not significantly higher than the score of 553 achieved when PIRLS first ran in 2001. It is also noteworthy how little the performance of high attaining pupils has improved, in contrast to Australia, for example, where the average score has increased by 17 points with improvements seen at both ends of the distribution.

The results provide a snapshot of the performance of a single representative cohort of the population, whose scores are affected by the cumulative impact of a wide range of educational and other factors. Without more detailed analysis of the results, it is premature therefore to attribute these improvements to the education reforms.

As well as providing a useful benchmark for the overall performance of the system, international studies such as PIRLS also provide a rich mine of data that allows strengths and weaknesses to be identified and potential solutions explored. The results also shine a light on pupils’ and teachers’ experiences of school. Here are a few more highlights from the findings:

- The study reveals that 49 per cent of pupils were reported by headteachers to be somewhat affected by shortages in reading materials. However, this figure hasn’t changed significantly since 2011 and shows little relationship to pupils’ achievement in reading.

- Schools in England seem to have much more emphasis on academic success compared to other PIRLS countries and, when comparing the emphasis on academic success between schools in England, this is strongly associated with outcomes.

- Fifty-one per cent of pupils had teachers whose responses indicated they were very satisfied with their jobs while seven per cent of pupils had teachers who indicated that they were less than satisfied. These responses showed little relationship with pupils’ reading outcomes.

- Over a third of pupils (36 per cent) were classified as feeling tired every day or almost every day and over half (53 per cent) as being sometimes tired. These percentages were greater than the international averages. 25 per cent feel hungry every day or almost every day, and it’s amongst this latter group that significantly lower reading scores are seen.

- Just over a third of pupils (35 per cent) in England were categorised as liking reading very much. This was partially based on how commonly they read outside of school. This was lower than the international average of 43 per cent. A fifth of pupils (20 per cent) were categorised as not liking reading (above the international average of 16 per cent).

NFER will be exploring the results in greater detail over the coming months, delving into the educational experiences of the Importance of Teaching class of 2010.

For more information on NFER’s work on international studies such as PIRLS, TIMSS and PISA, visit www.nfer.ac.uk/international