Prudent planning or imminent crisis? Data on school reserves in Wales reveal complex picture

Tuesday 23 October 2018

The latest figures for school reserves in 2018 released last week by the Welsh Government show that some schools have accumulated reserves totalling £50m while others show a deficit totalling £25m. But are schools really sitting on money while others are in deficit or is the headline figure masking a more complex picture?

This blog post delves deeper into what these figures tell us, highlighting issues such as why some schools are holding reserves, what are the drivers for the differences, and what the implications are for the Welsh schools system?

In 2017, Wales’ Education Secretary Kirsty Williams admitted to being ‘shocked’ by the amount that schools were ‘holding on to for a rainy day’ – hadn’t they understood that ‘it’s raining now’? On the other hand, teaching unions have warned that a recent drop in reserves was the symptom of an imminent funding crisis in schools.

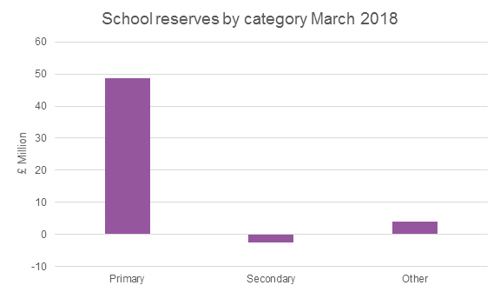

Primary schools have more in reserve than secondary schools

The figures in this latest release confirm a pattern evident over the past five years – namely that primary schools hold most reserves, to a point where this year a total of £48.7m (97 per cent of all reserves held by schools) are held in reserves by primary schools. Even so:

- 146 (11 per cent) primary schools were in deficit with a combined deficit of £4.2m

- In another 585 (45 per cent) primary schools the level of reserves is less than 5 per cent of their delegated expenditure.

Worryingly, the aggregated figure for all secondary schools reveals a deficit: although 122 secondary schools have combined reserves of £15.9m, the other 79 (39 per cent) have a combined deficit of £18.3m. This reinforces the message from headteachers last year that secondary school budgets were already stretched.

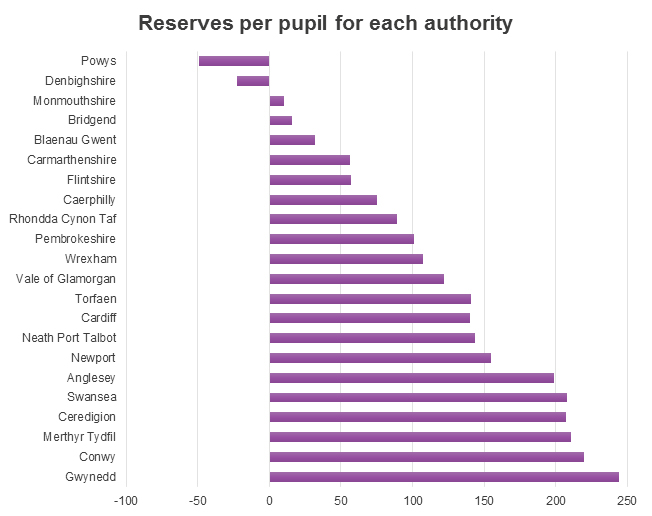

The amount of reserves per pupil varies by local authority

The release of these official figures highlight the differences in funding levels across Wales, which in 2017-18 ranged from an average of £6,456 per pupil in Powys to £5,107 in the Vale of Glamorgan. Interestingly, there does not appear to be an observable link between the overall level of funding per pupil provided by local authorities through the Direct Schools Budget and the level of reserves held by their schools. This is illustrated starkly in the case of Powys which set the highest per pupil level of delegated school budget in the 2017/18 financial year but reported a deficit of £49 per pupil in March 2018.)

Figure 1.2

Source: Welsh Government Statistical First Release

In 2017-18 the average level of reserves in schools in Wales equated to £111 per pupil. However:

- this was substantially higher in some authorities, including Gwynedd, Conwy, Merthyr Tydfil, and Swansea

- the level of reserves was lower in other authorities, including Monmouthshire, Bridgend, and Blaenau Gwent

- in two authorities school budgets were in deficit -(£23 per pupil deficit in Denbighshire and £49 per pupil deficit in Powys)

- there are also noticeable differences within Welsh local authorities (LAs)

- the aggregated secondary school budgets were in deficit in ten of the 22 Welsh LAs.

These variations in the level of reserves may, of course, be explained by other factors such as the historic level of funding in different authorities: schools in areas which have had a higher level of funding in the past may have been able to accumulate reserves over time, unlike schools in authorities which have increased their level of per pupil funding more recently.

Looking beneath the figures

Any consideration of the amount reserves held by schools needs to acknowledge the differences in school context. For example, some schools may have set the money aside to fund projects such as specific capital projects, strategic appointments in the future, succession planning, or because governors considered it better for money to be put into reserve rather than spend hurriedly during the financial year in which it was paid to the school.

Schools may also be augmenting their budgets through the deployment of staff (for example, by seconding staff for other duties within regional consortia). Given the emphasis on a school-led model of improvement in Wales, such practices are likely to increase rather than diminish in future.

The published figures do not provide sufficient information to judge whether the recent increase/decrease in school reserves is a good or a bad thing. The type of contextual information which would be helpful includes:

- whether the same schools are holding reserves year-on-year

- the impact of historic levels of funding on whether schools have accumulated reserves

- the impact of factors such as the size of a school, the age profile of its staff and schools’ decisions about staffing levels (including the appointment and deployment of support staff).

However, it is clear that in future most secondary schools in Wales will not be able to sustain their existing level of provision by using reserves, as their budgets are already in deficit. Secondary headteachers have already warned that that this could lead to larger classes, less choice for learners (in particular at GCSE) and that it could also jeopardise the introduction of the new curriculum. More than half of their primary colleagues may also be wondering how long they will have any reserves available to supplement their budgets.