Regional Schools Commissioners and the performance of multi-academy trusts

Thursday 5 November 2015

Substantial and increasing numbers of English schools are run by Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs), and yet we currently have no consistent and agreed upon method for assessing how well these MATs are performing.

This is one of the issues that was touched upon during yesterday’s Select Committee hearing on Regional Schools Commissioners (RSCs), which I was invited to appear before.

There are a variety of types of MAT (see this excellent overview), but typically they are groups of schools operating under a common governance and accountability structure. The smallest contain just a couple of schools, and could be formed when one successful school takes on the sponsorship of a neighbouring school that is struggling. The largest contain dozens of schools across the country, are often referred to as ‘academy chains’, and have a head office and regional infrastructure concerned with everything from procurement through to curriculum and pedagogy.

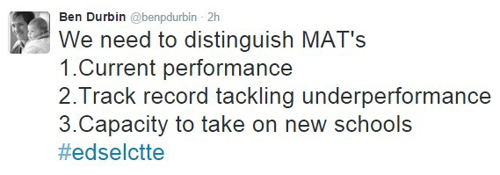

So, given the growing importance of their role (around one in seven of all state-funded schools in England are part of formal multi-academy groupings, and over half of all academies are), how should we measure the performance of MATs? The answer, as ever, depends on the question behind the question, as I tweeted as the Select Committee session drew to a close.

Allow me to explain. We may be interested in the current performance of MATs as part of the accountability system, and to support mechanisms by which underperformance is identified and tackled. In which case we need to come up with some sort of aggregate measure of the performance of all the schools in the MAT. Ideally we would also take into account the length of time each school has been part of the grouping. For example, it would be unfair to penalise a MAT for the poor performance of a school that it has only just taken on that year, especially where the very purpose of this move could be for a successful MAT to turn the school around.

There are already a few examples of exactly where this has been done, such as by the Sutton Trust and in a statistical working paper released by the Department for Education.

However, returning to the focus of the Select Committee’s inquiry – the role of RSCs – our recent report illustrates the scale of the challenge they face in identifying new sponsors (such as MATs) to take responsibility for underperforming schools. We estimate there are typically around seven schools requiring attention for every existing sponsor with the potential to respond. (The report also provides an introduction to RSCs, if you – like many – are still unsure of their role.) Indeed, the three RSCs who appeared before the committee yesterday emphasised these challenges.

In this scenario we are less interested in a MAT’s current performance – it’s possible that all of their schools are outstanding simply because they were already outstanding when they joined. Rather, we should consider the MAT’s track record in turning around underperforming schools. Do they have any experience in taking on struggling schools, and if so what happened to those schools in the years that followed?

Finally, even a MAT with a strong track record in tackling underperformance may not necessarily have the capacity right now to take on more struggling schools. It could be that they have already recently taken on several, and therefore for the next year or two will need to focus on these in order to replicate their past success. It is equally possible that some existing MATs are unwilling to respond to RSCs’ requests, such as smaller groupings preferring to remain small or larger chains wary of the real or perceived pitfalls of over-expansion.

Assessing organisational capacity will rightly draw heavily on the RSCs’ expert judgment, but as a guideline, one useful measure would be the proportion of the schools currently in the chain with performance below key thresholds. Indeed, this is one of the factors we built into the sponsor analysis in our report. A sponsor’s capacity may also depend on the nature of the school requiring intervention – for example, different skills may be required for primary versus secondary schools – and on its geographic location.

The Education and Adoption Bill looks set to further expand RSCs’ responsibility for so-called coasting schools. Developing better measures of how groups of schools are performing and their potential for taking on new underperforming schools is therefore critically important both for monitoring the performance of our education system and for delivering improvement in schools which are falling behind.

The Select Committee have their work cut out when it comes to making recommendations on the role of RSCs. But if they could focus on just one thing, they could do a lot worse than provoking a more meaningful discussion of these issues.