The kids are alright

Thursday 11 December 2014

Last October, the headline finding from England’s performance in the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) was the low literacy and numeracy skills of people aged 16-24.

The skills of England’s young people were below those of young people in most other participating countries, middle-aged adults in England and even the oldest cohort of adults in England age 55-65. This finding was widely interpreted by journalists and policymakers as bad news for young people’s prospects in the labour market and a damning indictment of the school system that had educated them.

The Department for Business Innovation and Skills asked NFER to dig deeper into the data and determine whether this interpretation was correct. Our research found a different story: the previous generation of young people also had low skills in their 20s, but their skills had improved once they reached middle age.

Here comes the science bit…

Skill differences between age groups measured at a single point in time are made up of a mixture of different effects, and there are two that dominate:

• The cohort effect is the set of underlying differences between generations, which are fixed over time, for example, differences in the schooling received as children.

• The age effect is the change in skills level in the same set of individuals over time,for example, we might expect declining skill levels in older adults.

The headlines that accompanied the PIAAC findings interpreted young people’s low skills as a pure cohort effect: the reason young people did so badly was because of their fixed characteristics. As Robert Peston, BBC economics editor, said at the time: “Those who moan that education standards have declined in Britain are correct, according to the OECD.” But could the results be explained by an age effect instead?

We combined the PIAAC data with a previous international survey of literacy skills, IALS, in which England participated in 1996. By comparing more than one snapshot we can separate the two effects because some generations are measured at two time points.

The cohort of 16-24 year olds in 1996 scored significantly lower on average than the 25-34 and 35-44 age groups. But when measured again in 2012, the same cohort (now age 32-40) scored 15 scale points higher: the same as the difference between England’s average and high performing Finland’s average in 2012 (note that they were not the same individuals, but the group of individuals was sampled from the same population).

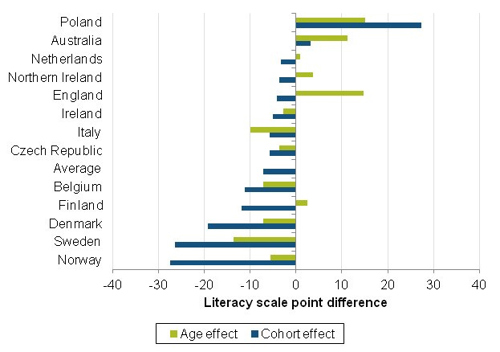

This suggests a skills gain: a rapid increase in the skill levels of adults after leaving full-time education and entering the labour market. As shown in the figure, it turns out the skills gain is fairly unique to England. This helps to explain why the skills of England’s young people are so low, while England’s overall average performance was similar to the average among all participating countries.

Our analysis showed that today’s young people have a slightly lower skill level compared with 16-24 year olds in 1996, but the difference is not very large. The cohort effect is therefore not a very good explanation for why England’s young people have low literacy skills. Other countries have much larger cohort effects, most notably the Scandinavian countries.

Note: the ‘cohort effect’ shows the difference between the average score of 16-24 year olds in 2012 with the average score of 16-24 year olds in 1996. The ‘age effect’ is the difference between the average score of 32-40 year olds in 2012 with the average score of 16-24 year olds in 1996. Selected countries are ranked by the cohort effect.

But, the picture is not necessarily all rosy

However, while the prospects for young people appear to be less bleak than was initially thought, there remains plenty of cause for concern. Why are young people’s skills so low in the first place? The existence of a skills gain in early adulthood could be indicative of young people leaving school without the skills to succeed in the labour market and having to develop those skills as they make their transition. In other words, the school system may not be teaching the types of skills that are valued in work, so young people have to develop them in the first years of their employment.

Additionally, the finding that the skills of today’s young people are no better than those of young people in 1996 should be seen in the context of the massive real-terms rise in school spending during the time they attended school and a large number of educational interventions aimed at raising standards. Should we have expected better? And if so, what went wrong?

Finally, the age effect only provides a forecast of the skills gain we might expect to see the current generation of young people experience, based on the experiences of the previous generation. But what if the skills gain doesn’t materialise? If the mechanisms that enabled the previous generation to increase their skill levels through their 20s are no longer accessible to young people, then low skill levels might endure into adulthood. Youth unemployment was 15 per cent in 1996 and dropped to around 12 per cent for the following decade: will today’s young people be able to ‘learn on the job’ with youth unemployment rates of 20 per cent (although the rate has recently dropped to 14 per cent)?

The challenge for skills policy is therefore to improve the skills of young people leaving compulsory education and to make sure UK businesses continue to make efficient use of those skills and to develop them further.