The latest findings from the Teacher Workload Survey 2019

Friday 25 October 2019

Earlier this month the Department for Education (DfE) published the findings from the latest Teacher Workload Survey (TWS), which was conducted by NFER in March this year. It is the latest evidence on teacher workload, which is a key priority for the DfE and remains an important issue for schools.

A key finding from the report is that teachers, middle leaders and senior leaders reported working fewer total hours per week in the 2019 survey, compared to the 2016 survey.

The report enables robust comparisons with the 2016 survey due to their identical methodology. In this blog we explore how the findings compare to the wider literature on teachers’ working hours and also look at other TWS findings that consider teachers’ perceptions of workload.

Estimates from different sources should be compared cautiously with one another because there are differences in sample design, sample size, question wording, time of year, etc. between all of the surveys. However, the TWS 2019 findings give grounds for cautious optimism about the direction that teacher workload is going, but also highlight that there is more work to do to reduce teachers’ working hours and to improve their experiences of work.

What does this new information add to what we know about teachers’ working hours?

The TWS found that, on average, primary teachers and middle leaders reported working 50 hours per week in 2019, down by 5.5 hours since 2016. Secondary teachers and middle leaders reported working 49.1 hours per week in 2019, down by 4.4 hours since 2016. The survey also finds that senior leaders reported working fewer hours per week than in the previous survey. These estimates are based on full-time and part-time workers combined.

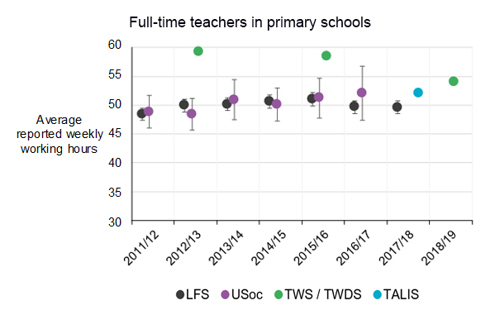

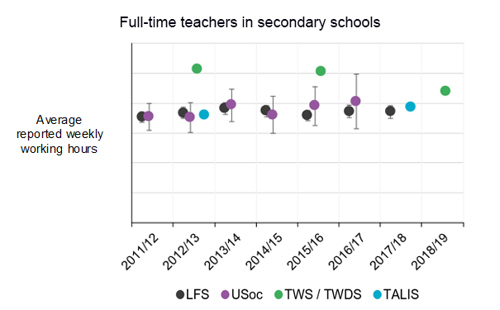

The TWS is one of a range of data sources that measure teacher working hours in England. The charts below show how the 2019 TWS estimate compares to those from the recent large-scale OECD TALIS international study and NFER’s analysis of data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and Understanding Society (USoc) survey.

As noted above, due to methodological differences, estimates should be compared with caution. However, they all attempt to measure the average weekly working hours of full-time primary and secondary teachers in England, and were sampled and weighted to be nationally representative. Note that as the comparisons focus on full-time teachers and middle leaders only, they differ from the headline figures on hours worked, which also include part-time teachers and middle leaders. Confidence intervals are shown to reflect differences in precision due to the respective sample sizes.

Note: dots show the estimate from the survey in that academic year. Bars show the 95% confidence intervals for LFS and USoc estimates – confidence intervals for TWS and TALIS are omitted, as they are so narrow that they are effectively invisible on the chart. All estimates measure total weekly working hours of full-time teachers in England. All estimates are state-sector only, except TALIS, which has small number of independent schools. All estimates exclude senior leaders. LFS and USoc estimates are based on hours worked during a “normal working week”, while TALIS and TWS are based on reported hours worked in a reference week. LFS and USoc estimates are based on respondents from randomly sampled households, with teachers identified from detailed occupation and industry codes. TALIS and TWS estimates are based on responding teachers from random samples of schools. The TWS 2013 was a paper diary survey (‘TWDS’), while the TWS 2016 and 2019 were online surveys.

Although there are fluctuations over time in all the surveys, the broad consensus from these studies over the last eight years is that full-time teachers work around 50 hours per week. The TWS 2019 estimate is in line with this consensus, while the TWS 2016 and its predecessor (the 2013 Teacher Workload Diary Survey) are significantly higher than 50 hours per week for full-time teachers. Comparing the TWS estimates with those from the wider literature emphasises the need for cautious interpretation of the trends at this time, until future studies have taken place.

The TWS 2019 is the first survey to measure teachers’ working hours in the 2018/19 academic year, and so represents the most recent data we have available. The fall in reported working hours found by the TWS may indicate an underlying downward shift in working hours that future surveys may confirm in time. There has been significant policy activity aimed at reducing teacher workload over the last year, including the DfE’s teacher workload reduction toolkit published in July 2018, which the TWS may be picking up.

The findings highlight the need to continue monitoring trends in teachers’ working hours. The DfE are committed to collecting robust evidence on teacher workload every two years (the three-year gap from 2016 and 2019 for TWS was to avoid clashing with TALIS in 2018). The next survey in 2021 will be an important part of this continued monitoring. NFER also intend to provide further monitoring and insights through our analysis of LFS data in our Teacher Labour Market annual report, the next instalment of which we will publish early next year.

Why have teachers’ working hours dropped?

The TWS is a valuable survey for understanding teacher workload for a number of reasons. For example, it goes beyond estimating the total number of hours that teachers work by also looking at:

- how teachers spend their time on different activities

- how they feel about the amount of time they spend on these various activities

- how they perceive their workload and its manageability generally.

The main factor driving the reduced total working hours in 2019 was that teachers and middle leaders reported spending less time on non-teaching activities compared to 2016. In particular, teachers and middle leaders reported spending less time on planning and preparation, marking, administration and, to a lesser extent, on data management.

This is significant as these reductions are concentrated in the areas of focus for DfE’s 2016 independent teacher workload review groups (marking, planning and resources, and data management) and 2018 workload advisory group (data management). The findings therefore suggest that the work of the review groups may have contributed to progress in reducing teacher workload.

Despite reporting spending less time on planning and preparation, marking, administration and data management, large proportions of teachers and middle leaders still reported that they feel they spend too much time on these activities. More than half of both primary and secondary teachers and middle leaders reported spending too much time on administration, marking and data management, and more than half of primary teachers and middle leaders reported spending too much time on planning and preparing lessons.

However, the proportions that reported spending too much time on these activities had all declined between the 2019 and 2016 waves of the survey, suggesting movement in a positive direction.

Improving teachers’ perceptions of their workload involves more than just reducing the number of hours they work

The findings show that teachers who reported working longer hours are generally more likely to report that workload is a problem. However, they also show that primary teachers and middle leaders - who generally report working longer hours than their secondary counterparts - are less likely to perceive teacher workload to be a ‘very serious problem’ in their school.

Taken together, these findings emphasise the complex challenges of improving teacher workload, and suggest that improving teachers’ perceptions of their workload involves more than just reducing the number of hours teachers work. Research by NFER and Education Datalab shows that the issue of unmanageable workload is more important than the hours worked in determining teachers’ job satisfaction and likelihood of staying in teaching.

More work is needed to reduce teacher workload

Around seven out of ten primary respondents and nine out of ten secondary respondents reported that workload is a ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ serious problem in their school.

Teachers’, middle leaders’ and senior leaders’ perceptions of their workload improved relative to 2016, but 74 per cent still reported not achieving a good work-life balance and 79 per cent reported not having an acceptable workload.

The TWS 2019 findings therefore give some grounds for cautious optimism about the direction that teacher workload is going. But they also highlight that there is more work to do to reduce teachers’ working hours and improve their experiences of work.

For more on NFER’s work in the School Workforce area, visit www.nfer.ac.uk/school-workforce