What impact did Covid-19 have on teacher retention?

Thursday 17 June 2021

In the second in a series of blogs on Covid-19 and the teacher workforce, NFER School Workforce Lead Jack Worth looks at teacher retention in 2020.

In the second in a series of blogs on Covid-19 and the teacher workforce, NFER School Workforce Lead Jack Worth looks at teacher retention in 2020.

We have seen from various data sources that the recession led to a surge in applications to postgraduate initial teacher training over the summer of 2020 and into this year (although that may now be waning as the wider labour market begins to recover). Survey evidence also suggested that teacher retention and turnover improved last summer (see NFER, Teacher Tapp).

Today, DfE published the first hard evidence to date of what happened to teacher retention in England last summer, following the first wave of Covid-19. What does the School Workforce Census data tell us about what really happened to teacher retention last summer?

Teacher retention improved considerably in 2020

The data measures the number of teachers who left between November 2019 and November 2020, covering the first period of school closures in the spring and summer and the full reopening of schools in September.

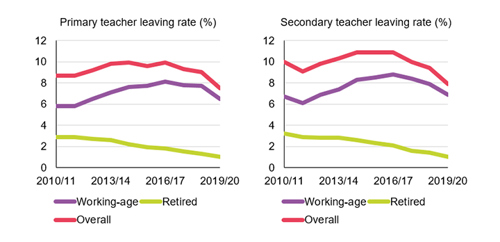

The data shows that the rate of teachers leaving fell dramatically in summer 2020, compared to previous years. Overall leaving rates had been rising steadily since the beginning of the decade for both primary and secondary teachers, peaking in 2014/15 before subsequent slight falls.

Covid-19 contributed to the overall primary teacher leaving rate falling from 9.0 per cent in 2019 to 7.5 per cent in 2020 and the secondary teacher leaving rate falling from 9.4 to 7.9 per cent. The overall number of teachers leaving fell by 17 per cent compared to 2019.

Teacher retention tends to improve during recessions, because job prospects outside of teaching become more uncertain compared to ‘recession-proof’ teaching. The lockdown may also have made moving job more challenging and teachers may have been reluctant to leave their schools in the lurch during a crisis.

Source: DfE School Workforce in England 2020.

During the last decade, the rate of teachers retiring had fallen steadily from around three per cent to less than two per cent, while the rate of working-age teachers leaving had climbed rapidly from around six per cent in 2010/11 to around eight per cent in 2018/19. The data shows that the retirement rate kept falling, to just one per cent, while the leaving rate for working-age teachers fell from 7.7 to 6.5 per cent for primary teachers and 7.9 to 6.9 per cent for secondary teachers.

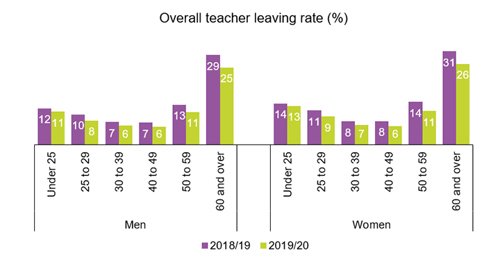

The data on leaving rates by teacher age shows similarly that there was a fall in leaving rates across all age groups and genders. We expect to see the highest leaving rates for the youngest and oldest teachers, but the decrease in leaving rates was fairly similar across age groups.

One group that stands out, however, is the under-25s, for whom there was not as big a change in leaving rate. The data shows that this was driven by leaving rates of newly-qualified teachers (NQTs) remaining high, despite retention of more experienced early-career teachers improving.

Source: DfE School Workforce in England 2020.

Early-career teacher retention has improved, except among NQTs

Retention of early-career teachers (ECTs) has been a key focus for policy in recent years, and is particularly relevant now as the reformed two-year Early Career Framework induction programme rolls out nationally from September. ECT retention had been a particular concern for the sector because of the high rates of ECTs leaving the profession.

The chart below shows the proportion of the remainder of a cohort of newly qualified teachers (NQTs) that left teaching in the state-sector in England in a given year. The red line shows the proportion of the NQTs who started teaching in a particular year, but left before the end of the next year. Fifteen per cent means that 85 per cent of the cohort remained in teaching at the end of their first year. The orange line shows the percentage change in the proportion of an NQT cohort that remained in teaching into their second year, among those who had made it to the second year.

Strictly it is not a leaving rate, since it also includes teachers from each cohort who returned to teaching in the state-sector in that year, but it gives a good indication of the attrition rate of teachers at each stage of their careers.

In recent years, around 15 per cent of the cohorts first entering teaching were leaving within their first year. Around eight per cent of those from the cohort who remained then left the following year (less those who returned, having left the previous year) and a six per cent of the remainder left in the next year. The cumulative effect of this high attrition was that more than a quarter of teachers (27 per cent) had left within three years and a third (33 per cent) had left within five years.

Source: DfE School Workforce in England 2020.

Similar to the pattern in overall leaving rates, ECT attrition rates had stabilised and begun to fall in the last couple of years after considerable rises during the early part of the decade, particularly for those in their first four years since entering teaching. Covid-19 has contributed to ECT retention rates falling in 2019/20, across most cohorts. The data shows that attrition among teachers in their second year fell from eight per cent to six per cent and among third-year teachers from six per cent to four per cent. Likewise, attrition of fourth-year teachers fell from five to three per cent and fifth-year teachers from four to two per cent.

However, in contrast, the proportion of the new NQT cohort that entered teaching in 2020 that left actually rose slightly, from 14.6 per cent to 15.5 per cent. This is somewhat of a surprise in the context of the overall downward trends, and the reasons may be worth investigating further.

One possible explanation is that schools, faced with an unexpectedly high number of teachers staying in their role in 2020, may have balanced their budgets by letting NQTs leave. Whereas most teachers are employed on permanent contracts, some NQTs are employed on a temporary basis, before moving to a permanent role after completing their induction. This temporary status may have left them vulnerable to being let go to save cost. However, there may be other possible reasons are possible, and this surprising finding is worthy of further investigation.

Crisis averted?

Set against the backdrop of the teacher supply challenge that England was facing in 2020, and coupled with the surge in applications to teacher training, it is tempting to think that improved retention has averted an impending crisis. Teacher supply challenges in the short-term have certainly been eased, and retention rates may continue to be slightly higher in the years to come due to the wider economy being subdued by the after-effects of Covid.

However, some of those who decided not to leave in summer 2020 may have simply delayed leaving until later. Indeed, there is some concern about high post-Covid headteacher attrition, given the strains that steering their schools through Covid may have taken on them. Might we see the attrition rate bounce back after the Covid crisis is over?

There are plenty of teacher workforce trends to continue monitoring into next year.