What the latest IELS findings tell us about young children’s development

Tuesday 1 December 2020

New findings from the International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS), published today by the DfE, have cast fresh light on the factors that help, and hinder, young children’s development.

New findings from the International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS), published today by the DfE, have cast fresh light on the factors that help, and hinder, young children’s development.

International comparisions and IELS results

In 2018, more than 2,500 5-year-old children from 191 schools across England took part in IELS, organised by the OECD. The results provide many insights into the factors associated with children’s physical, cognitive and social-emotional development.

IELS found that the development of 5-year-olds in England differed notably from the other two countries in the study, Estonia and the United States. In England, children showed stronger development in emergent numeracy and positive behaviour compared to overseas, while for emergent literacy, working memory and mental flexibility, they showed similar development to Estonia and greater development than the United States.

Broadly speaking, at age 5 children in England had similar development to children in Estonia – the highest-performing OECD country in the PISA study at age 15 – and showed greater development than their peers in the USA.

Looking at the data collected by IELS has also helped us understand far more about 5-year-old children’s physical development, the importance of persistence, and the extent of the development gaps that are already present by this age in England.

The study used two types of assessment: interactive stories and games completed by children on a tablet computer, and reports on children’s development from parents and teachers. This allowed researchers to gather a full picture of their capabilities without children feeling stressed or placed under pressure.

Physical development and the effects of the pandemic

As we count the cost of the Covid-19 pandemic on children’s wellbeing, these findings feel particularly important. The recent Ofsted report looking at the impact of the lockdown on schools highlights this issue, suggesting that some children have experienced declines in several areas of their development, including their physical development.

To be clear, physical development as measured in IELS was in line with the Early Years Foundation Stage. It included gross motor skills, such as the ability to run and jump, to climb, throw and kick, and to do so under control. It also included fine motor skills; small movements in the hands and wrists which control the child’s ability to use a pencil to draw shapes and numbers, to use scissors to cut around a shape or even to put on a coat without help.

Deprivation and gender are both strongly related to children’s physical development at age 5, with those eligible for free school meals an average of eight months’ behind their more affluent peers, while girls were an average of nine months’ ahead of boys in their physical development.

With children from economically deprived backgrounds more likely to have suffered obstacles to their physical development from the recent Covid-19 lockdown, it is vital to identify and support children who need more help. Of course, there are existing programmes which can help here, like the Nuffield Early Language Intervention, which provides online training and resources at no cost for those schools where additional targeted support for oral language would be particularly beneficial.

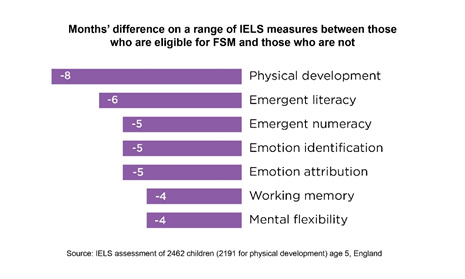

Eligibility for free school meals (FSM) was not just a risk factor for physical development; IELS found that those children eligible for free school meals were behind their peers across all measures aside from inhibition. Inhibition – a measurement of a child’s ability to inhibit an impulsive response in favour of an alternative response – showed no statistically significant difference between children eligible for FSM and those who were not.

The impact of low birthweight

However, a particularly interesting finding was the influence of one risk factor that is less well recognised. The study investigated the influence of low birthweight on children’s development (often associated with premature birth); information which is not routinely collected by schools or investigated by educational researchers.

We found that children whose parents had reported them as having low birthweight (2.5kg or less) had statistically significantly lower levels of emergent literacy, emergent numeracy, working memory and physical development compared to their peers.

Of these measures, poorer physical development was the most strongly related to low birthweight, equivalent to a difference of approximately 9 months of development. However, low birthweight was not significantly related to development in any of the social-emotional measures in IELS.

The importance of persistence

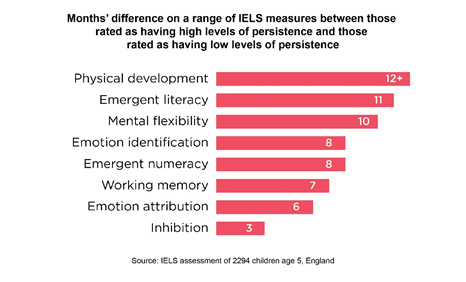

Conversely, IELS also highlighted the potential importance of a child’s persistence which was significantly related to all of the outcome measures. Teachers were asked to rate each child’s ability to overcome obstacles when attempting tasks and this was shown to be strongly linked with early development.

Children rated as ‘often or always’ persistent were more than 12 months’ ahead of their peers considered ‘rarely or never’ persistent in physical development, 11 months’ ahead in emergent literacy, and 8 months’ ahead in emergent numeracy.

These results highlight the importance of perseverance for young children. Although we are unable to say whether this comes from innate personality, upbringing, or a combination of the two, it seems likely that encouraging children to be persistent when tackling obstacles will stand them in good stead.

Finally, IELS has revealed that children’s development in one area is related to development in almost all others – a finding that will doubtless ring true to early years and primary teachers. In particular, emergent literacy was strongly related to emergent numeracy, and both were strongly related to mental flexibility, working memory and emotion identification (a key part of empathy). Prosocial behaviour was strongly related to trust and non-disruptive behaviour, and physical development was strongly related to prosocial behaviour and trust.

The IELS report gives us new insights into children’s development at the age of five, as well as the importance of persistence, and the interrelations between children’s development across cognitive, social-emotional and physical domains. These can be tools to better identify which children are more at risk of struggling earlier in their lives, and to offer more targeted support to them, as well as highlighting what we can do to give children the best start. We now need policy makers to work with schoolsto use these vitally important findings to tailor their own offers, and ensure every child has the chance for a fulfilling life.

NFER was contracted to carry out IELS in England by DfE. However, this article has been produced solely by NFER and does not necessarily reflect the views of DfE