New survey research sheds light on teachers’ and leaders’ working lives

Wednesday 12 April 2023

Today the DfE published the findings from the inaugural Working Lives of Teachers and Leaders study – a major new longitudinal survey of over 11,000 primary and secondary teachers and leaders working in English state schools.

Today the DfE published the findings from the inaugural Working Lives of Teachers and Leaders study – a major new longitudinal survey of over 11,000 primary and secondary teachers and leaders working in English state schools.

The survey, which was conducted in Spring 2022, covers a range of areas, including working hours, workload and satisfaction with pay.

At a time when many teachers are striking over pay, the findings shed light on teachers’ and leaders’ self-reported working conditions.

Leaders’ working hours appear to be on the rise

The findings reveal that for a specific ‘reference week’ in Spring 2022, defined as the respondent’s ‘last working week covering Monday to Sunday that was not shortened by illness, religious breaks or public holidays’, secondary leaders reported working longer hours on average than their primary counterparts (58.3 vs. 56.2 hours for primary leaders, on average). These figures are averaged across both full and part-time workers, and as primary leaders are more likely to work part time than their secondary counterparts, this partially explains this difference.

Amongst full-time leaders, those working in primary and secondary schools reported working longer hours than those in special schools, pupil referral units (PRUs) and in alternative provision (AP).

Conversely, secondary teachers reported working slightly fewer hours on average than primary teachers (48.5 vs. 49.1 for primary teachers, on average).

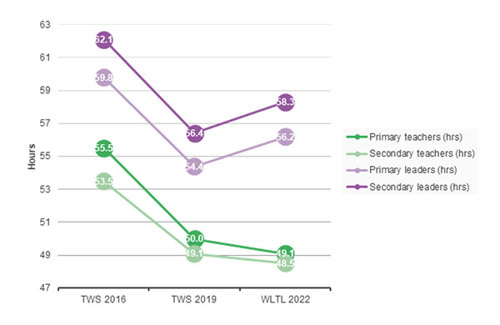

We can explore how working hours have changed over time by comparing the findings to previous estimates of teachers’ working hours captured in the 2016 and 2019 waves of the Teacher Workload Survey, with the latter wave being undertaken by NFER. While caution should be taken when comparing findings between surveys, they suggest that leaders’ working hours have risen in recent years, while teachers’ working hours continue a downward trend (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Average teacher working hours in the reference week have fallen since 2016, while leaders’ working hours fell between 2016 and 2019 and rose in 2022

While teachers continue to work longer hours than similar individuals in other professions, the findings showing a decline in workload represent a move in the right direction for teachers and may reflect efforts that have been made in recent years to reduce unnecessary workload. This started with the 2014 Workload Challenge and more recently, in the collection of practical resources for schools contained within the school workload reduction toolkit, although there is still a way to go.

While average working hours for leaders remain lower than reported in 2016, the rise since 2019 is a cause for concern, particularly following ongoing concerns regarding leadership recruitment and retention. It seems likely that this rise is associated with the additional workload pressures leaders’ have experienced as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, with disruption still being felt today. However, given higher workloads contribute to teacher and leader leaving rates, this rise needs to be addressed, as the sector can ill afford to lose its experienced leaders. Leaders’ workloads also need to be made more manageable if headship is to be viewed as an attractive and aspirational role for the next generation of school leaders.

Satisfaction with workload remains low, particularly among headteachers

Historically, survey questions asking teachers about their workload have solicited largely negative responses. The findings from WLTL continue this trend, with 72 per cent of teachers and leaders reporting that their workload is unacceptable. This represents a slight increase compared to the TWS 2019 finding of 69 per cent, but a fall from the high of 88 per cent reported in the TWS 2016 (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Teachers’ and leaders’ level of agreement with the statement, ‘I have an acceptable workload’, in 2016, 2019 and 2022

Perhaps not surprisingly, those who reported working longer hours were more likely to say that their workload was unacceptable. More experienced teachers and leaders were also more likely to say that their workload was unacceptable than less experienced staff.

First year early career teachers (ECTs) were the most likely to agree that their workload was acceptable, despite recent evidence suggesting that the Early Career Framework had added considerably to ECTs’ workloads.

At the other end of the spectrum, headteachers, and particularly primary headteachers, were the most likely to say that their workloads were unacceptable.

Other subgroups that were more likely to express dissatisfaction with their workloads included those reporting poor pupil behaviour at their schools and those teaching at schools serving more affluent catchments.

Those working in special schools, PRUs, and AP were relatively more positive about their workload compared to those in other settings, suggesting their experiences of working life may differ to those in mainstream primary and secondary settings.

Most teachers and leaders are not satisfied with their level of pay

Given the current industrial action, it is interesting to see what the WLTL says about teachers’ and leaders’ views about their pay. Most teachers and leaders (61 per cent) indicated they were dissatisfied with the salary they receive for the work they do, while around a quarter (26 per cent) indicated they were satisfied.

Satisfaction with pay was higher amongst those in more senior roles, presumably because these groups are paid the most. This is supported by the fact that headteachers and executive headteachers were more satisfied than deputy and assistant headteachers, who would typically earn less. Satisfaction was also higher amongst older teachers and leaders, and specifically amongst those aged 55+.

There was little difference in views on pay between those working in primary and secondary schools, but those working in a special school, PRU or AP were more likely to be satisfied with their pay than others. It is unclear to what extent this reflects differences in average pay across these settings, and/or their improved conditions relative to staff in other settings (e.g. lower hours for senior leaders, and teachers’ and leaders’ greater satisfaction with their workload).

It is important to note these views were collected during the early stages of the current cost of living crisis, and ‘real’ disposable incomes have since fallen further. For example, the Consumer Price Index inflation rate was about eight per cent at the time the survey was completed but peaked at 11.1 per cent in October 2022.

Final thoughts

Workload and working hours are significant factors affecting teacher and leader retention. While an increase in pay may help with the recruitment of teachers, we need to further reduce teachers’ and particularly leaders’ workloads if more teachers and leaders are to be retained within the profession.

The WLTL findings suggest that while some improvements have been made to the working lives of teachers and leaders, they are not spread evenly across the teaching workforce. Policymakers would be wise to be mindful of these differences when developing policy so that improvements can be targeted where they are most needed.