Is ‘what works’ enough?

Friday 19 April 2013

I’ve just read Ben Levin’s latest paper To know is not enough: research knowledge and its use (in the new online journal – Review of Education, 1: p2 to31). I am delighted to see the current and growing interest in better evidence and better use of evidence. Hardly a day goes by recently without something interesting arriving in my inbox relating to either or both of these, and this change in climate opens up new opportunities and potential partnerships with like-minded others. We can all achieve so much more if we work together.

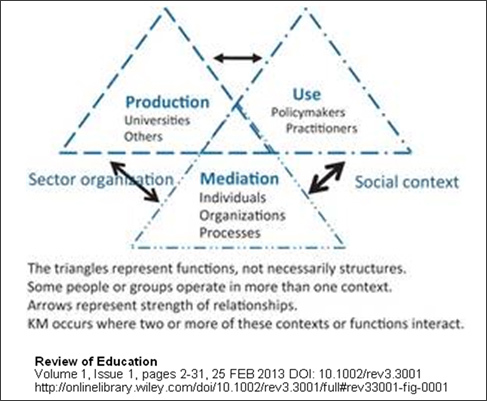

I like Levin’s simple model of the three contexts – research production, research use and research mediation and, particularly, the overlap and inter-dependence of these three aspects in relation to what he calls ‘knowledge mobilisation’.

Some thoughts on research production

As others have said already (see Ben Goldacre), knowing what works is only part of the answer. Knowing why, how and when something works is perhaps more important; and knowing what you need to do to try this out in your own school or service and being motivated and supported to do so are critical.

In the current climate there is a small danger of some seeing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as the only worthwhile approach to gathering evidence. To do so would be to miss out on the other forms of evidence which, if used appropriately, can also enrich understanding of whether and how to do something differently. These include: evaluations which look more closely at how a change has been implemented and why it might have the effects seen; systematic research reviews and syntheses which bring together all of the evidence on a topic and indicate what weight can be attributed to different findings; even local practice examples which have some underpinning evidence of success can point the way to changes worth investigating further. (See also Daniel Willingham)

We need clear standards of evidence for all of these different types of research, and to understand what can be said – and with what certainty – from the different sources of evidence.

I doubt that we need new bodies charged with producing evidence or syntheses – there are plenty of organisations, including my own, that can (and do) do this well. But we do need to agree methods for organising and sharing evidence so that a teacher or school leader knows how and where to look for the best evidence on a particular topic.

Creating a rich evidence base, brought together in ways that make relevant information readily available is perhaps the easy part. We need to think much harder about how to increase the interest, motivation and capacity of so called research users to do something with it.

Some thoughts on research use

We would benefit from a shared view of what the important questions are – and for whom. And to be truly meaningful and relevant, the importance of such questions can only really be determined by answering more fundamental questions – what is our shared view of the purpose of education and hence what would an effective education look like in this country. Of course, these fundamental questions take us into political and philosophical domains but some shared – or at least broadly held – view must be important.

We need a shared and quite detailed view of how to interest and engage teachers and other practitioners in the value, use and creation of evidence – a theory of change. This is an under-researched area but a working version of a national model or theory would be of benefit – based upon what IS known already, and constantly updated as new evidence emerges of how good evidence can impact on practice.

NFER’s interest in this whole area is because we are a charity, charged with providing independent evidence that improves education and learning and hence the lives of learners. So as well as producing good evidence, we are keen to see that evidence plays its proper part in decision making about education, in Whitehall and in each classroom, school and service. Others who have invested large sums in research, such as the Education Endowment Foundation, are also keen to find ways to ensure that relevant findings are taken up at scale.

Unless there is a widely shared, holistic and self-sustaining approach to increasing educational research usefulness to leaders and practitioners, the current surge of interest in what works and in evidence-informed practice will not make a lasting difference. History tells us this would not be the first time.

This suggests at the very least some leadership or coordination is needed, given the many players involved. The Alliance for Useful Evidence (NESTA) promotes the notion of more ‘What Works’ centres to improve the links between the supply of evidence and the demand for and use of evidence. How such centres coordinate and draw from the work of the many players in educational research is unclear, as is the relationship with representative user bodies such as any future Royal College of Teachers. The latter, for example, might take on a leadership role in developing research user capacity within the teaching profession.

Wherever this system leadership debate leads, we should grab the opportunity of this ‘Evidence Spring’ to create significantly better alignment between what researchers do and the needs of service managers, teachers and others who want to provide the best possible education and support for children and young people.