What are we to make of the latest School Workforce statistics?

Friday 1 July 2016

At a time when trainee targets are being missed, retaining the teachers already in the profession becomes all the more important. Teacher retention has been the focus of a programme of NFER research, including our Should I Stay or Should I Go? report last November and forthcoming research examining the experiences and intentions of teachers.

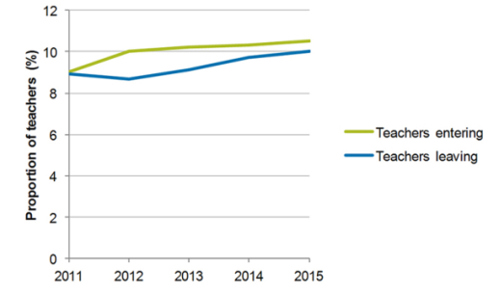

Yesterday’s School Workforce statistics show that the rate of teachers leaving the profession has jumped to the highest level since 2011, with 10 per cent of teachers having left between November 2014 and November 2015. In terms of teacher headcount, the proportion of teachers leaving is the highest since at least 2005.

More teachers are leaving but overall teacher numbers are stable

There are some reasons to think this should not be a great concern. The leavers were replaced by even more joiners, as they have been every year since 2011, and the rate of teachers leaving is only one percentage point higher than it was four years ago. The overall number of teachers has increased again this year, suggesting that where vacancies arise they are largely being filled.

Pupil numbers are expected to grow fast in the next decade, especially in secondary schools

However, there are good reasons for thinking this situation is concerning. What the overall number of teachers and the data above on teachers joining and leaving does not tell us is anything about the level of demand for teachers. One factor that will affect teacher demand is whether pupil numbers are changing. The number of pupils has been growing over the same period, and the pupil-teacher ratio has risen, albeit marginally, from 17.8 in 2011 to 18.1 now.

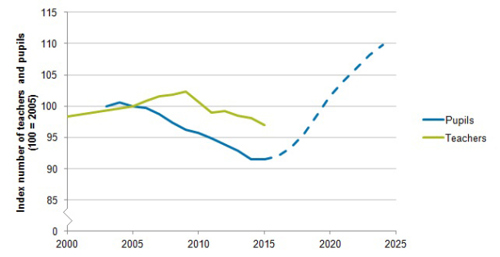

The growth in pupil numbers is expected to accelerate over the next ten years, particularly in secondary schools. The chart below plots the change over time in the number of secondary school pupils and the number of secondary school teachers, including the current projections of pupil numbers up to 2024 (dashed line). The level of each in 2005 is set to 100 and changes are relative to that initial level. Following an increase in the number of teachers relative to the number of pupils in the 2000s, the pupil teacher ratio has been relatively stable as teacher numbers have tracked pupil numbers since 2010.

However, it is secondary schools that have seen more teachers leave than join for the past two years despite pupil numbers that are growing again. The downward trend in teacher numbers will need to reverse quickly to meet the coming growth in pupil numbers.

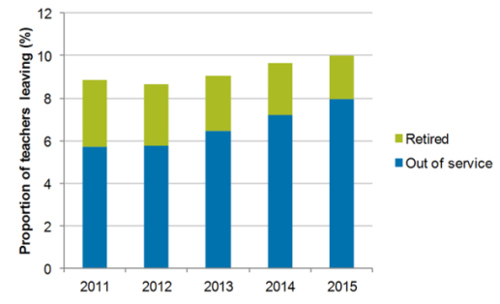

Retention of working age teachers is getting more difficult

Another concerning factor is that the proportion of teachers leaving and not retiring has increased more rapidly, from 6 per cent of teachers in 2011 to 8 per cent in 2015. Overall, this has been offset by a reduction in the number of teachers retiring, but suggests that retaining working-age teachers is becoming harder.

Detailed workforce statistics on the retention rate (i.e. the proportion of teachers still in the profession) of teachers that qualified at different times and have different levels of experience, show that retention rates are lower this year across the board. The retention rate of teachers after three years in the profession has dropped from 80 per cent in 2010 to 75 per cent in 2015, the five-year rate has dropped from 73 per cent to 70 per cent and the ten-year rate has dropped from 64 per cent to 61 per cent. While small changes, they indicate that teachers of all ages are becoming increasingly mobile, whether due to ‘push’ factors from teaching as it is today or ‘pull’ factors from the wider labour market.

What might we expect in future?

Research on the effect of wider economic conditions on teacher supply suggests the current strong situation in the labour market is bad for retention and worse for recruitment of trainees. Scotland and Wales are also reportedly experiencing problems encouraging enough new trainees into teaching, which suggests that common factors (such as the economic environment) are important as well as any factors that are unique to England (e.g. the changing system of different routes into teaching) at explaining under-recruitment.

The number of applications for teacher training soared following the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession. If, as many economists expect, employment prospects in the private sector deteriorate as a result of the UK leaving the European Union (or at least the uncertainty created by the referendum result), then we may yet see an increase in graduates and others entering ‘recession-proof’ teaching. Time will tell if this offers a partial solution to the teacher supply shortage.